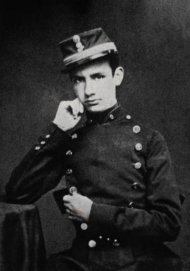

HM Francis II, King of the Two Sicilies

HM Francis II, King of the Two Sicilies, is the last. Under his reign, the Kingdom was invaded first by the Garibaldian army, then by the Savoy army and later annexed to the newborn Kingdom of Italy. All this, only one year after the death of Ferdinand II, who died aged 48, and Francis unexpectedly ascended the Throne aged only 23.

He was born on 16 January 1836, elder son of Ferdinand II and his first wife Maria Cristina of Savoy (whose canonization is now in progress), who died when he was only 15 days old. His father, together with his second wife, Queen Maria Teresa of Habsburg, and the help of the Jesuit fathers, gave him a strongly religious education and the rudiments of general knowledge, but he never had the military education that Ferdinand had received. However, Ferdinand taught him the love for his Kingdom and his duties for his subjects, who had priority over everything else after God. His relations with his stepmother were difficult – because she gave priority to her own children (she had 11 children, among which Alfonso Maria, Count of Caserta, Head of the Royal House after Francis’ death) – but never turbulent: Francis respected the Queen and she respected him as Crown Prince.

Ferdinand chose Maria Sofia of Bavaria – daughter of Duke Maximilian and sister of Elisabeth, wife of Francis Joseph Emperor of Austria – as Francis’s wife. Maria Sofia turned to be an exceptional woman in the tragic days of their lives. Her subjects would never forget her and all Europe admired her.

The early days were not easy for the Court to Maria Sofia, destined not to be understood with the Queen, but had on the contrary all the sympathy of the King, that he was sincerely attached. The problem was just that with his arrival in Naples, Ferdinand began to get ill, the elevation to the throne of Francis and Maria Sofia made it even more critical relations-wise with the Queen Mother, but now other problems were preparing to emerge, and Mary Queen Sofia proved to be strong and courageous like few others in history: the thoughts can not go to Marie Antoinette of the last days of his life, and although Maria Sofia fortunately was spared the tragedy of his death and of her husband, a slower grief was chosen by most for the rest of his long life (he died in 1925).

In reality, Francis could reign only for one year; then he had to face the invasion of his Kingdom. However, despite his short reign, he could show what his reign could have been if he had reigned as peacefully and long as his predecessors.

Francis was certainly not endowed with his father’s strong character, nor did he possess his political experience, but he was very humane and magnanimous, he had a deep faith and a sense of duties towards his subjects, especially the needy ones. He joined the reformist approach of his predecessors and a deep sense of religious duties, which perhaps made him the best king for his subjects. Moreover, the strong pro-Bourbon resistance of the ‘60s that involved tens of thousands of men and women – as at the time of the uprising – who rose up to defend their king’s lawful rights, is the best evidence of what we have just said.

Since his coronation, Francis gave many amnesties, appointed special committees to improve the situation of prisons, granted a greater local autonomy to municipalities, and also streamlined bureaucracy. He granted customs franchise to Palermo and Messina and established a Commercial Court and Savings Banks in Catania.

He remitted customs taxes still due, halved the tax on flour and abolished that on farmhouses where poor people lived and reduced customs duties, especially the tax on foreign books. He also diminished taxes on foreign goods, established an Exchange Office in Chieti and Reggio Calabria, ordered the opening of pawnshops, wheatshops, saving and loan banks in those cities that did not have any of them. Since the kingdom had been affected from a wheat shortage, while the rebels were blaming the King of putting the burden on the poor, he ordered the distribution of wheat stocks – that the government had bought from other countries – to the population at a very low price, with a clear economic loss for the government. Moreover, he founded universities, high schools and boarding schools and he established a commission to improve the town planning of Naples (to this end he was planning new government-owned steam mills to offer free grinding, but the arrival of the Garibaldian troops stopped his plans); he enlarged the railroad system, personally controlled and asked liability for the delays of private firms in the fulfilment of construction contracts already passed, and by royal decree of 28 April 1860 he ordered the construction of the Naples-Foggia and Foggia-Capo d’Otranto railroads; then he ordered the construction of the Basilicata-Reggio Calabria railroad and the Abruzzi railroad, and he was already planning a railroad for Palermo, Messina and Catania.

On 1 March 1860 he ordered waterworks for all lands and in so doing he avoided the formation of marshes and fostered field irrigation and public health; he ordered the drainage of the Fucino lake, the embankment of Sarno river by digging a navigable channel, the continuation of work in Neapolitan marshes and the clearing of Sebeto mouth. All this was made in just one year. In 1862, when he was exiled in Rome, he sent a huge amount of money to the Neapolitans who had been victims of a violent eruption of the Vesuvius.

After the fall of the Kingdom, the royal couple was hosted in Rome by Pius IX (who in this way could repay the courtesy and hospitality received by Ferdinand II in 1848-1850) first at the Quirinale and then at Palazzo Farnese, until 1870. In those years, they tried to foster the pro-Bourbon resistance that was taking roots in their former Kingdom, but then they realised that they had lost and did not want to cause other bloodsheds, hatred and pain.

Deprived of their personal assets by the Savoy (with no right or justification, Garibaldi had seized not only their intangible assets but also their tangible ones, that Francis did not want to take with him), they had to move often, and lived for many years in Paris, and once so often they went to Bavaria, to Maria Sofia’s family estates, and led a modest and serene life. In one of these travels, in 1894, in peace with God, his neighbours and therefore his conscience, Francis II died at Arco (Trento). He did not leave any heir, and therefore his brother Alfonso Maria of the Bourbon of the Two Sicilies, Count of Caserta, became Head of the Royal House.

The invasion of the Kingdom

It is not possible to relate here the entire history of the Risorgimento, the conquest of the Kingdom by the Piedmont army. We can just say that today’s many historical reconstructions of the events of those days are more serene, true and objective than the “official version” provided by history in the past 140 years. Many historians (and not only pro-Bourbon ones) are nowadays doing an honest reconstruction of the tragic events of the invasion and conquest of the Kingdom. Here we just list the most credible and unquestionable historic achievements, well known by experts but still ignored by the large majority of Italians and foreigners, who are still influenced by their school memories concerning the heroic conquests of Garibaldi’s army and a southern population exulting for being “liberated” by the “Bourbon’s uncouthness”. Today nobody still relates these stories, but they are still alive in the imagination of many. However, the reader that was patient enough to read carefully the previous headings has by now realised that the anti-Bourbon “vulgata” is full of lies and is antithetic to historical truth.

We do not want to engage ourselves in a controversy, but we must pay a service to historical truth and to the common memory of the Italian people, and therefore we just want to mention the most important and unquestioned (although not yet known by everybody) historical acquisitions on these events.

- Already in the 50s, and in particular in 1858 by the Agreements of Plombières, Cavour had planned – with the support of Great Britain, Napoleon III and Italian democrats – the invasion of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the seven-centuries old independent State, a peaceful state and an ally, a friend of the Kingdom of Sardinia, whose last King was cousin of King Victor Emanuel II;

- Napoleon III supported Cavour in the hope (which turned to be a chimera) that the Kingdom would go to his cousin Luciano Murat, whereas Great Britain hoped that a new friend and grateful Kingdom of Italy could oppose both the French and the Habsburg predominance (moreover, the Anglican world had concrete hopes of “evangelising” Italy, still victim of the “papal superstition”);

- Garibaldi, for his expedition, received men, ships and most of all weapons by the Kingdom of Sardinia, whereas money came in plenty from Great Britain and international Masonry [It is 3 million French Francs (given to Garibaldi as Turkish golden piastres in Genoa before the boarding) and 1 million ducats (exorbitant figures) to Admiral Persano, to which we must

- add 300,000 golden lire provided in Milan by banker Garavaglia and directly given to Garibaldi. See A.A.-V.V., Un tempo da riscrivere: il risorgimento italiano, Mostra di Rimini 2000, Il Cerchio, p. 21. For this matter, see also the very good work of R. MARTUCCI, L’invenzione dell’Italia unita, Sansoni, Firenze 1999].

- This money was used to corrupt the highest ranks of Bourbon Officers, who since the landing in Sicily never fought seriously Garibaldi’s soldiers (think that Garibaldi arrived in Naples by train! And his army reported only a few casualties and injured people in all), and wickedly delivered fortresses and military posts to the invaders; but this money was also used to corrupt the most important statesmen, who always advised Francis II in the worst possible way and then openly betrayed him, as it was the case of Liborio Romano, Prime Minister and first traitor of the king;

- Cavour ordered Admiral Persano, commanding the Savoy fleet, to follow the expedition from a distance and help Garibaldi if everything went well; which was the case;

- Great Britain did the same and deployed the whole fleet in fighting trim in the Gulf of Naples while Garibaldi arrived, a clear sign of what could have happened if Francis II had tried any resistance;

- While Victor Emanuel II assured his friendship to his Neapolitan cousin and deprecated what was happening, Cavour ordered General Cialdini to take the army to Naples and take possession of the Kingdom (and what is more, by invading the Papal State), and the Savoy King himself went South to receive from Garibaldi the Kingdom he had conquered (they met at Teano);

- Napoleon III, who condemned the expedition in public and said it was an action of international piracy (and no definition could be better indeed), in secret gave his approval to Cavour by a statement that has become famous: “Faites, mais faites vite!”, and in exchange demanded Nice and Savoy for his non-intervention;

- Francis II, alone in front of one of the largest international conspiracies in history, and, most of all, betrayed by his officers and statesmen and most loyal and closest advisors, understood that nothing could be done, but that he could not loose his honour and historical memory: to avoid civil bloodsheds, he left Naples and took refuge in Gaeta’s fortress, followed by those who voluntarily chose to save their honour and fight on the side of their lawful and loved King who had been attacked.

The Fortress of Gaeta

The siege of Gaeta was one of the most tragic and heroic events in the history of Risorgimento. While leaving Naples on 8 December 1860, Francis II issued a proclamation of which we quote some passages: «(…) I preferred to leave Naples, my own house, my beloved capital city, not to expose it to the horror of a bombing, such as it later happened in Capua and Ancona. I believed, in good faith, that the King of Piedmont who maintained he was my brother and my friend and disapproved of Garibaldi’s invasion, who negotiated with my Government a close alliance for the true interests of Italy – would not break all agreements and infringe all laws to invade my peaceful dominions without reasons or war declarations. If these are my faults, I prefer my misfortune to the triumph of my enemies» [In: “Gazzetta di Gaeta”, 9 December 1860, n° 21, p. 1]. This proclamation frightened the chief of police of the Lieutenancy, Silvio Spaventa, since, as reported by Ruggero Moscati, «it caused a great emotion in large strata of southern populations» [R MOSCATI, I Borboni d’Italia, ESI, Napoli 1970, p. 153].

In fact thousands of loyal subjects assembled in Gaeta (at the same time, also the fortresses of Civitella del Tronto – which was the last to fall – and Messina were strenuously and heroically resisting), ready to die to defend their King [Roberto Martucci acknowledged the merits of Francis II and reported the wrong-doings of the opponent historiography that portrayed him as “Franceschiello”, and reported also the following passage by A. ARCHI (Gli ultimi Asburgo e gli ultimi Borbone in Italia (1814-1861), Cappelli, Bologna 1965, p. 376): “Francis II was a misfortuned king and his misfortune lasted even more than the few months of his real rule: he could not withdraw his money from banks, and he could only bring with him devout objects and family memories from the Palace, but not artistic or valuable works”. MARTUCCI, op. cit., pp. 189-190] and their country and to testify the faith and civilization of their fathers and show by their actions their refusal of a corrupted and treacherous society to which they did not want to belong.

The history of the tragic resistance of Gaeta, besieged by a ruthless man, is well known and many books relate it. The siege began on 13 November 1860 and lasted until 13 February 1861. It was carried out with an extreme ferocity and Cialdini dared to bomb even the room where the royal couple lived, in the clear hope of killing them.

Here we just quote the following moving words used by Roberto Martucci in his description of the atmosphere in which the siege occurred, and especially the last days of the siege and the feelings of the losers – devastated by hunger and plague – who knew they were inculpable victims of an aggression that none of them had wanted and heroic defenders not of a Kingdom, but of a centuries-old civilisation. He also wrote about the laughs of the winners, bitter laughs anyway: «On 5 February 1861, a bullet hit Sant’Antonio powder magazine and caused about hundred casualties and buried alive hundreds of soldiers under its ruins. “The enemy – Pietro Calà d’Ulloa wrote- made a human sacrifice to the infernal gods; the last explosion flung soldiers and officers up in the air and then down in the sea; the besiegers, in Mola, applauded as they were watching a show” [P. CALA D’ULLOA, Lettres d’un ministre émigré, Marseille, 1870, p. 80].

After a short truce to extract the wounded from the ruins, Cialdini refused to grant a respite that would have consented the rescue of other victims still alive; the Sardinian General resumed the bombing and at the same time offered the exhausted Neapolitan garrison an unconditional surrender. Facing the uselessness of further resistance, Francis II authorised the Governor of Gaeta – the very General Giosué Ritucci who had led the unlucky counteroffensive at Volturno River – to negotiate the surrender. It was 11 February, the negotiations went on for two days and general Cialdini never stopped bombing the unlucky fortress with all his artillery; on the contrary, he took advantage of the negotiations to make operative other two deadly batteries of cannons. Since the surrender was certain, further deployment of artillery was deadly useless. Provided he was not victim of that syndrome that the French novelist Jules Verne has brilliantly described in his novel “From Earth to the Moon”, when the prostrated engineers and ballistic experts of Baltimore “Gun club” learnt with sorrow that the end of the War of Secession prevented them from experimenting the efficacy of the bullets of their cannons on the confederated army. And so, in Gaeta, at 3pm on 13 February, while Neapolitan and Sardinian negotiators were discussing the last details of the surrender, the Transylvania powder magazine and its 18 tons of explosives exploded. The Piedmont artillery immediately concentrated their fire on the ruins to prevent any rescue, and machine-gunned the stretcher-bearers. Two officers, 50 soldiers and the whole family of the guardian died uselessly. The Bourbon plenipotentiaries negotiating the surrender at Cialdini’s Headquarters hardly held back their tears while their hosts loudly applauded, infringing the rules of hospitality and the unwritten laws of military honour» [MARTUCCI, op. cit., p. 195].

Cialdini, not yet satisfied, wanted to be sarcastic to humiliate those who had bravely and dignifiedly resisted him, and generously offered the royal couple a ship to go to Rome: he chose a ship called “Garibaldi”.

Among the tears of soldiers and officers kneeling in front of them and the tears of the population, Francis II and Maria Sofia shook hands with everybody, smiling yet with tears in their eyes, and then set sail to Rome.

«At that time Francis of Bourbon was only 25, Maria Sofia was 19, yet in their misfortune they were able to show dignity and strength of character that older and more toughened sovereigns would hardly possess». Sergio Romano commented: «If these were the new battalions of the unified Italy, once assuming the government of the new State, the new ruling class had to feel at least the need to pay respectful homage to the stubborn Bourbon defenders of Messina, Civitella del Tronto, Gaeta, and at least add their names to the “list of heroes” whose memory had to be revered. Like the Swiss at the Tuileries in 1792, those men fought because they had sworn loyalty to their king and did not deserve the oblivion to which they were condemned by the Risorgimento tale» [S.Romano, Finis Italiae. Declino e morte dell’ideologia risorgimentale. Perché gli italiani si disprezzano, Milano, 1994, p. 15].

The Royal couple left the harbour of Gaeta to the sound of Paisiello’s royal march and saluted by 21 cannon salvos, while the whole population cried and waived hands. In this way, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies came to an end, leaving millions of southern peasants stupefied and without a homeland, whereas most of the notables planned to ask a new position suitable to their class and needs in the new political and administrative system of the unified Italy and were already putting aside the little money by which they would take possess of the lands of aristocrats loyal to the king and of the Church and then financially ruin millions of peasants who would never know again piety and humanity and for whom the sole means of escape became emigration.

We cannot relate here the misfortunes that fell on Southern Italy after 1861 and for which it exists still today an unresolved explanatory definition that hangs over the history of Italian unification like Damocles’ sword: “southern issue”.

All historians agree in saying that the heroic behaviour of Francis II during the siege of Gaeta redeemed him from all his real or presumed political weakness. We could quote many moving historical opinions in his favour; but we prefer to quote, for all, the objective and more aseptic opinion of an unquestionable and certainly not pro-Bourbon historian. Giuseppe Coniglio wrote: «However, in the eyes of history he was able to redeem his failures during the siege of Gaeta, in which he audaciously took part, and showed Europe that he knew how to act and fully succeeded in this, although supported by his wife’s model and encouragement. The royal couple could have easily succeeded in escaping (…) But Francis II did not want to bend to this humiliation and preferred to fight for a long time, thus obtaining military honour – even in the opinion of his enemies – for him and for all the defenders of Gaeta» [G. CONIGLIO, I Borboni di Napoli, Corbaccio, Milano 1999, p. 460].

We want to close this page by rendering honour to HRH Maria Sofia Queen of the Two Sicilies [Martucci described Maria Sofia of Bavaria as follows: “Sister of Empress Elisabeth of Austria – the famous Sissy – Maria Sofia, fascinating and short-lived Queen of Naples, during the long siege was a nurse for the wounded, fearless walked on the bastions among the cannons, always smiled to soldiers, always had a good word to give courage to that suffering people…” MARTUCCI, op. cit., p. 194], real leading spirit of the siege of Gaeta, rescuer of the honour of the Kingdom and the Bourbon Army: she spent every single day by helping her soldiers under the cannon shots, healing their wounds, sharing their fears and difficulties, encouraging them, feeding them, supporting them as she was supporting and encouraging her husband in the most difficult moments.

In Gaeta, the royal couple gave the best of themselves, the best of their love, dignity, devotion, self-denial, and honour, sense of duty towards their country, but also serenity and love for their soldiers.

Gaeta will remain forever in the history of the Bourbon Two Sicilies and in the history of the Kingdom of Naples, in the history of the Italians and in whole history as a page full of glory dignity and honour. Thousands of volunteers signed this page, ideally joined by the other volunteers who in the same time were fighting in Messina and Civitella del Tronto – the other two bulwarks of the Bourbon resistance that were taken only by fierce storm – even without the presence of their sovereigns. These people put their signature with their blood and honour after the signatures of the young royal couple, Francis II and Maria Sofia of Bourbon Two Sicilies.